This report will disappoint you, you’ve been warned. Too fragmentary and inconclusive. People want to know, I know. You have to give full explanations, or be silent; I know.

I will come back to this subject, I promise, but I’ll need to travel, collect materials, talk with people. It will take years. For now these notes, picked up on the internet and scraped from the bottom of my memories as a student will have to be enough. I have some books on the subject that would be very useful to me, locked in dusty boxes in a garage in the dry Northern Californian hills.

I must go on by heart. Me, the one that forgets to buy bread and take the shirts to the laundry.

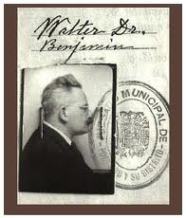

On September 26, 1940 Walter Benjamin dies, in Portbou, Catalonia.

Cerebral hemorrhage, states a medical certificate that no one believed.

Suicide, they say, to avoid falling into the hands of the Nazis who were on his trail.

There are witnesses. Not of the moment of death, but of what has happened in those days, before and after. Morphine overdose, some said. Thirty-one sleeping pills, said others.

Walter Benjamin was a writer, well known in intellectual circles, though not so much to the public. Today he is more popular. A Marxist, the most eccentric that ever existed. A literary critic, a scholar of Kabbalah and art history, a scrupulous observer of the effects of hashish, which he generously experimented with on himself and noted in accurate and detailed protocols. The list of famous friends who shared his circles would be lengthy, so I will state one name only: Bertold Brecht.

German citizen, jew, twenty-eight changes of address within seven years of exile in France, first in Paris, then more and more towards the south, never separated from the small newspaper wrap which contained sixty-two sedative tablets no policemen could confiscate, but that would have been enough to end it quickly when needed. A glass of water and it’s over.

A few weeks before the day of his death, Benjamin had come to Marseille, where he met several acquaintances, including his writer friend Hannah Arendt. There he was assured a visa to the United States. To collect it, however, he would have to move to Spain, which could only happen clandestinely. There he met a young woman, Lisa Fittko, and her husband Hans. Lisa was not a guide and did not know the territory either, but as a result of an urgent and flattering friendship with a local officer she had received a rudimentary hand-drawn map that revealed a passage through the mountains, through which she believed she could invisibly lead a group of defectors to Spanish territory.

The passage was rough, barely visible, hidden by rocks, blocked by landslides. The soldier who had sketched up the map had suggested they walked the first half of the road during the day, pretending a stroll, came back quietly like normal tourists in the afternoon; and at night, knowing the route better, retraced it in a real escape. The plan included Lisa Fittko, Walter Benjamin, photographer Henny Gurland and her son Joseph.

Benjamin showed himself at this pretend walk dressed with a starched collar, tight teacher’s jacket and a heavy suitcase, which he said contained a manuscript, more important than his person and his life. He proceeded, panting for hours, with its heavy burden in his right hand, in his left hand, in the two hands together, and finally on his shoulder, along that path that turned out almost impassable. He was forty eight years old, but looked ten years older. The companions looked at him, worried. They knew that his heart was sick.

When it was time to go back, Benjamin refused. Pale, panting, rings under his eyes, he said that he would sleep there, among the pine trees, and he would wait for their return the following morning.

The next morning they reached the pine trees and found him cold, darker rings under his eyes, barely able to keep pace with them on the rest of the way, that was all steep uphill. They still managed to reach the top of the mountain, from which they saw Spain and the Mediterranean. Three men were waiting for them in the valley below, as they appeared they threw their hats in the air. They were in Spanish Territory. Walter Benjamin collapsed and had to wait for the three companions to bring water, and drag him on their shoulders down to the plain, and on to the village.

Walter Benjamin had a unique punctuality in meeting his own destiny. On the exact day that he crossed the Spanish border, immigration laws changed. Everyone who entered had to be detained, the police withdrew his Spanish transit visa. Without the document, the jew Benjamin would have been extradited to France, at that time occupied by the Nazis, and immediately interned in a labor camp.

This law was canceled soon after. The very next day they were made broad exceptions. As Hannah Arendt wrote: “One day before and Benjamin would have entered without any problem; a day later and friends in Marseille would have known that it would not be possible to enter Spain legally. Only on that particular day was the catastrophe possible.”

Of the visa for the United States that had been promised as imminent, which should have already arrived at his secret Spanish address, there was no news. They say he panicked. That he was terrified of what the Nazis could do to him. Arthur Koestler, who had met him some time before, writes about the time when Benjamin took the newspaper wrap out of his pocket and divided his precious nepenthe in half, handing him thirty-one pills, in the silent, resigned and hasty ceremonial performed by those who do not want to attract attention.

Thirty tablets were enough, if we are to believe this version of the story.

The U.S. visa arrived the next day. If the wing of the angel of death had waited one night, Benjamin would have lived many more years, a respected intellectual in exile in New York or Los Angeles. If. How many ifs.

Possible is just what happens, Kafka wrote; a writer that Benjamin read and studied all his life. And also, there is salvation in abundance. But not for us.

As a student, I happened to bring his little book to a university exam: aesthetics.

The title was almost longer than the book: The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility. His thesis: simple, charming and mysterious. Of a painting by Leonardo we have a unique copy. Of a photograph by Man Ray, as many as we want. A photograph is technically reproducible.

Can we say that something is lost when a work of art can be reproduced? Yes, says Benjamin: its aura. What the aura is he does not define clearly, leaving us with obscure descriptions such as a strange web of space and time; or a distance as near as possible. We remain uncertain whether it is something in our mind, a kind of respect that magnifies the value of pieces of art, or a physical characteristic of the objects themselves, such as the spheres and circles around the head of the Buddhas and Madonnas that certainly mark an infinite distance, no matter how close they may be.

I remember that as a student, this topic, undefined and immeasurable as it was, convinced me immediately. Some time later, I read that he had said about Van Gogh something like, he directly depicts the aura of things. Now that I live in Amsterdam, and with my blue card I can go in and out of museums, and on Sunday afternoon I take a quarter of an hour to savor three pictures, I must say that I see it. I can see as a ghost the fiery soul of Vincent Van Gogh, his restless eyes that pierce the material veneer of things, to go to immerse themselves in a world of energy, alive and dangerous, direct, stinging, an immersion in quicklime, a war of complementary colors that leaves no solid ground under your feet and can not coexist with the network of painstakingly shared descriptions in which we wrap ourselves and we call mental health; and in the long run puts our lives in danger.

For most of his life Benjamin kept hanging in his studio, in front of him, a painting by Paul Klee called Angelus Novus.

The angel is wrapped in an undeniable aura, suspended in an expression of helplessness, pity and terror. Seems about to retrace his steps, possessed by suffering and compassion for what he sees. The nightmare of war, history, the Nazi horror, the extreme turn of the nature of man. He must endure the whole weight of this vision. We just see him.

“This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past.” said Gershom Scholem, a great friend of Benjamin, “Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. ”

What we call progress, concludes Scholem, is this storm.

I have not yet addressed the most confusing part, the one where even suicide is doubtful. Now I have to do it.

I know very little. Fragments that I can only pick and list. That the husband of Lisa Fittko was later recognized as a Stalinist spy. That the border between France and Spain at the time was swarming with spies to get rid of any intellectual with dangerous theories. Both proved to be associated with an organization called New Beginning.

That the husband of Henny Gurland was equally involved in New Beginning. That the man who had discovered that difficult path in the mountains, Colonel Lister, was also an associate.

That Henny Gurland says that on the morning of September 26, in the tiny hotel in Catalonia in which they were half guests and half prisoners, Benjamin sent for her in his room. That he opened the door, drawn and sweaty, saying that the night before, at exactly ten o’clock, he had taken enough morphine to knock down a horse. And shortly after he fainted in front of her, and never recovered.

Several people have commented that it is unlikely that you take an overdose of morphine at ten in the evening and suffer the effect only the next morning.

Benjamin had left her letters addressed to his closest friends, that Henny destroyed for security, and that only after weeks she rewrote, raking through her memory, in French – a language that Benjamin would never have used – That in those letters he described Portbou as a small village in the Pyrenees, whereas it is a fairly large town and not too close to those mountains, something that Benjamin knew well.

That no one ever found the suitcase with the precious manuscript. Some say the manuscript was called Philosophy of History, and that it contained a rejection of Marxism and a harsh condemnation of the work of Stalin. Mr. Koestler, who had spoken of sixty-two sleeping pills in his book, in other writings speaks of fifty and in another of thirty- three. That Koestler was in the spotlight of the Stalinist counter-espionage is proven in numerous files. Benjamin and Koestler had spent a lot of time together in Marseille, in public places, playing poker and telling each other their life stories; that is certain. That the agent Rudolf Roessler, code-named “Lucy”, kept an eye on him for a long time. Anyone who followed Koestler inevitably stumbled on Benjamin. I imagine Roessler looking at a photograph of the two men sitting at an outdoor café while dividing a bunch of tablets. Sixty, at a guess.

That immediately after his death the expulsion order was revoked and those who traveled with Benjamin were allowed to stay in Spain. Benjamin was buried with Catholic rites in the Catholic section of the cemetery at Portbou, although it had a Jewish area. That when his friend Hannah Arendt came to visit the tomb four months later, it was impossible to find any grave or any trace of the name of Benjamin.

Walter Benjamin wrote a story dedicated to the angel who had been in front of him for a lifetime. He named it Agesilaus Santander, in German an anagram of Archangel Satan.

If I remember correctly, the story ends with the phrase – I want to return with you to the future from which we came.